When Provia turned blue

And what I did to get the correct colors back!

When Fuji released the new Provia 100F

film, I gave it a try and was hooked by its extremely fine grain, combined

with generally good performance. I made it my default film. All went well

for some time, but Provia 100F was never easy to get here in Chile. Supply

is erratic, and often outdated film is sold, at prices well above what fresh

film costs elsewhere. So I started importing my film from the US. Having

the film processed was another problem. Slide film use has been going down

in Chile, and at this time in my 120,000 inhabitant city there is no

single lab that would process slides! So I had to send the films to Santiago,

and often wait for a full month until getting the slides back!

That was bad enough. But one day I got a box of blue slides from the lab.

The sky was nice deep blue, but the clouds were light blue, the gray pavement

was bluish, the grass was green-blue, skin was a pretty funny but ugly pale

color, you get the idea... The entire film was screaming BLUE !!!

I didn't like that at all. I threw my slides into the trash can, and decided to never trust that lab again.

The next film went to a different lab. When it came back, surprise! Would you guess that it came out... blue?

It was at this time when I started suspecting that the film was from

a bad batch, or had been damaged in some way. But to discard the labs as

the reason for my Provia blues, I shot some test pics and sent that

film to the third and last lab. You won't guess how the film came out!

No, not blue! This time it was a greenish blue!

At least this hinted at the labs being indeed the source of the problem.

During a trip to Santiago, I visited them in person and asked the obvious

questions. Of course, sir, we use only fresh chemistry. Of course, sir, we use only high quality Kodak chemicals. Of course, sir, we care a lot for the proper temperature and pH. Of course, sir, we run test strips every day. Of course, sir, no other client has ever complained about bad colors. I showed them some of my slides. But these look very nice, sir, the colors are perfect!

Sure, blue clouds on blue sky. And blue grass. That may be good enough

for music, but not for photography! I reminded them that the worst kind of

blindness is not wanting to see, and left, pretty enraged, I must say.

I had heard that color film processing, and specially slides, was touchy

and quite complex. But I started to read about it. I learned that modern

E6 processing is a lot simpler than it used to be. Just to try, I had my

amateur radio friend Carlos, XQ2PPA/OK2PPA mail me a pack of Tetenal chemistry

good for six rolls, from the Czech Republic. After all, I had a Jobo tank

and spools, and could set up some temperature control.

The Tetenal kit arrived, the box pretty deformed and flattened during transport,

but the contents was fine. The instructions started with the recommendation

of using only stainless steel hardware, because plastic could adsorb traces

of the chemistry and contaminate the other baths. Oh well... my tank and

spools were plastic, and smelled of B&W chemistry. My photographer friend

Felipe, at that time still residing in Santiago, purchased and sent me a

100% stainless steel tank with two spools.

My first trial run of home slide processing was boldly done with films from

a vacation trip. After all, sending them to the "professional" labs would

likely ruin them, so I figured that I could as well ruin them at home...

I ran the process strictly as explained by the instructions that came with

the Tetenal kit. Temperature control was a bit handmade, timing was by stopwatch,

and agitation was by hand reversal every 15 seconds, which made me feel my

stupid arthritis.

When I opened the tank, I expected anything... But what came out was some

milky film, which was expected (it clears up while drying), but the black

looked black and the white looked clean white... I hung it up to dry, and

when it was ready, the slides looked perfect! No trace of a color cast! I

felt like a birthday kid!

I never learned if the blue results from the commercial labs were a product

of sloppiness, or if Provia 100F reacts badly to Kodak chemistry. Anyway,

I don't care now. The remaining slides of the trip were processed in the

same chemistry, and then I bought a 60-film kit of the same Tetenal chemistry,

which even was available in Santiago.

But I didn't want to spend an afternoon inverting the steel tank every 15

seconds, every time I had a few films to process. So I decided to build...

...a homemade semiautomatic Rotary Film Processor!

Before deciding on building such a machine, I looked at what's available

commercially. There are many options, most of them made by Jobo, but a machine

with reasonable features is depressingly expensive! A simple processor which

is nothing more than a plastic tank, heater, thermostat, circulation pump,

and rotation device for the tank, costs 5 times as much as a fully featured

computer-controlled automatic laundry machine that has all these things and

several more, and is several times larger and more powerful! The prices seems

rudely out of proportion!

Before deciding on building such a machine, I looked at what's available

commercially. There are many options, most of them made by Jobo, but a machine

with reasonable features is depressingly expensive! A simple processor which

is nothing more than a plastic tank, heater, thermostat, circulation pump,

and rotation device for the tank, costs 5 times as much as a fully featured

computer-controlled automatic laundry machine that has all these things and

several more, and is several times larger and more powerful! The prices seems

rudely out of proportion!

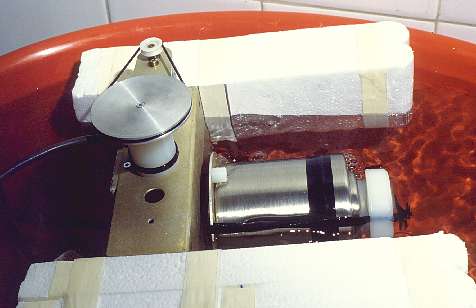

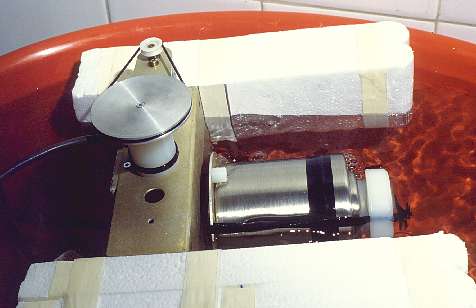

So, home brewing was in order, and the project was quickly executed. The

photo shows my homemade rotary processor on its first use. It consists of

two main assemblies: The red baby bathtub with heater, temperature sensor,

circulation pump, bottle holders, floating deck with the rotation mechanism,

is one. I place it conveniently on the kitchen sink. The other is the electronic

control unit, which sits on the desk at left, safe from water splashes.

Most commercial processors lack the capability for providing tempered rinse

water. But all color processes require rinses with tempered water! So, the

poor guys who buy a 1000 dollar machine need to spend additional money for

their controlled warm water supply! To get rid of such a problem, I used

a 30 liter bathtub as a container, and simply take water from it for the

rinsing. To compensate for the falling water level as the processing takes

its way, the rotation device is mounted on styrofoam floats, cut from the

packaging of my latest computer, thus holding the tank always at the same

level of immersion.

Most commercial processors lack the capability for providing tempered rinse

water. But all color processes require rinses with tempered water! So, the

poor guys who buy a 1000 dollar machine need to spend additional money for

their controlled warm water supply! To get rid of such a problem, I used

a 30 liter bathtub as a container, and simply take water from it for the

rinsing. To compensate for the falling water level as the processing takes

its way, the rotation device is mounted on styrofoam floats, cut from the

packaging of my latest computer, thus holding the tank always at the same

level of immersion.

The plastic baby bathtub cost me a whopping 3 dollars!

I mix the chemistry in plastic half-liter soft drink bottles. I label them

simply with small scraps of masking tape: One scrap for the first bath, two

scraps for the second, three for the third - it's idiot proof, and the masking

tape is totally waterproof. The half-liter portions are good for 6 films,

and I use them up on a single day. The chemistry doesn't last long once mixed

and used - the first developer starts precipitating only hours after making

first contact with film! If the concentrates last long enough, I may be able

to use the full 60-film capacity of the kit, but that remains to be seen.

I would need the concentrates to last vastly longer than the promised six

months, in order to use them up. Anyway, I use butane gas from a camping

stove to displace air before closing the concentrate bottles. In the first

photo, you will notice the open door. It's because of the butane, and also

for the fumes given off by the chemistry, which are not very dense, but still

not exactly healthy to breathe.On the other hand, most of the time all containers

are closed. Only during filling and emptying the tank, can fumes escape.

The stainless steel tank has no sealing, just metal-to-metal contact. So,

it leaks. And that's not nice. For that reason, I wrap the main joint in

electrical insulating tape. I use Scotch 33+, which is the best I have found,

and not only for this purpose. Highly recommended! It can be re-used many

times in this application. The tape not only seals the joint, but also eliminates

the risk of the tank opening due to a handling accident, and thus ruining

the films inside.

The stainless steel tank has no sealing, just metal-to-metal contact. So,

it leaks. And that's not nice. For that reason, I wrap the main joint in

electrical insulating tape. I use Scotch 33+, which is the best I have found,

and not only for this purpose. Highly recommended! It can be re-used many

times in this application. The tape not only seals the joint, but also eliminates

the risk of the tank opening due to a handling accident, and thus ruining

the films inside.

To seal the small lid of the tank, I made a silicone seal by pouring silicone

caulk into a polyethylene mold. Both this seal, and the electrical tape,

are external to the tank, so contact with the chemistry and thus the risk

of contamination is minimized.

The rotation device is made on an old radio chassis. It uses a small tape

loading motor from an old VCR, while all the pulleys, axles, bushings and

the tank holder were made on my lathe. A two-stage belt reduction is used,

the lower belt running underwater and over two auxiliary rollers that allow

coupling the vertical drive axle to the horizontal tank axle. The vertical

drive axle allows to keep the water off the motor.

The tank is clamped to the rotating platform by the rubber-band-loaded

white plastic piece at the right, which has the precise shape of the tank's

lid and silicone seal. Mounting the tank takes half a second longer than

when using a magnetic mount, while dismounting it is much easier than with

a magnet. The mount is strong enough that the full tank can be lifted out

of the water by the rotation assembly, which is then held 90 degrees tilted

for easy tank handling.

The black box with the label is the circulation pump. It's intended for indoor

fountains, and I bought it for around 15 dollars at a Home Center. It is

fully submergible and runs directly off line voltage - a reason to be very

careful not to damage its cord! This pump maintains a vigorous agitation

of the water bath, resulting in very homogeneous temperature.

The black box with the label is the circulation pump. It's intended for indoor

fountains, and I bought it for around 15 dollars at a Home Center. It is

fully submergible and runs directly off line voltage - a reason to be very

careful not to damage its cord! This pump maintains a vigorous agitation

of the water bath, resulting in very homogeneous temperature.

The snaking black tube is the heater. It's a 1950 Watt heater sold as universal

spare part in stores that service washing machines. It cost about 12 dollars,

and comes with its own expanding rubber seal, making it easy to obtain a

watertight fit. The power level may be a bit oversized, but that has the

advantage that the tub can be filled with cold tap water, and the heater

will quickly bring it up to working temperature. Once that temperature has

been reached, the high power is irrelevant, since the controller provides

fully linear phase control.

The rod with the cable coming from its end is the temperature sensor. It

uses a laser trimmed precision digital sensor, a DS18S20, that costs 5 dollars.

It's accurate enough to require no user calibration in this application,

and has a resolution of 1/16th degree Celsius. The sensor chip is immersed

in the oil that fills the copper tube, so it gets reasonably good and fast

thermal contact. Where the cable leaves the tubing, I pressed in a custom

made silicone seal, so no oil can seep out. A number of layers of shrink-wrap

stiffens the connection.

The controller is based on a Basic Stamp microcontroller. It contains several

film processing algorithms in memory, which can be selected from a menu.

The controller performs temperature control using a proportional-integral

characteristic and full phase control of the heater, resulting in fast warmup

time with minimal overshoot, and stable processing temperature. The temperatures

do not need to be set by hand, but rather they are included in the program

for each process.

The controller is based on a Basic Stamp microcontroller. It contains several

film processing algorithms in memory, which can be selected from a menu.

The controller performs temperature control using a proportional-integral

characteristic and full phase control of the heater, resulting in fast warmup

time with minimal overshoot, and stable processing temperature. The temperatures

do not need to be set by hand, but rather they are included in the program

for each process.

It also controls the timing, displaying the remaining time for each of the

chemical baths, and beeping when the time is over. The wash cycles are not

timed, giving the user time to do them as he likes, rather than becoming

a slave of the time machine!

The rotation can be controlled by a switch (lower right), and the speed is

adjusted by the knob on top from about 20 to 70 rpm. The rotation sense reverses

every 30 seconds, with 1 second stop time in between.

The lower left switch controls the circulation pump, while the top left switch

is for main power. The two red pushbuttons have the functions of select and enter

while using menu functions, but both perform the same function when starting

the timing of a bath, so it doesn't matter which one you press!

The display as pictured here tells us that the selected process is Tetenal

E6, 3-bath, first pass, that the temperature is 17.18 degrees Celsius, and

that the process control is in preheat phase (of course, at that low temperature!).

The top line always keeps indicating a reminder of the process, and the current

temperature, while the bottom line tells which phase is running, how much

time remains in the current phase, and what has to be done next. Pretty idiot

proof. I made it for my own use, after all... :-)

An additional nice feature of this controller is that it can use a 12V battery

for backup, so that a power failure will not result in ruined slides. While

the chance of a power failure during processing is slim at my location, it

gives peace of mind to have that battery backup!

If you want to build your own processor based on this design, you can access

the construction article for this controller in the

Electronicus section, complete with the schematic diagram and the control

software. But be warned that this device uses several electrical devices

submerged in water, and you may well find yourself with one hand in the tub

and the other hand grasping a grounded water faucet. This creates the single

most dangerous situation you can possibly come across in the electrical world!

If you want to build such a processor, it is mandatory that you know what

you are doing, and that you do it right. That includes bonding all metal

pieces, sound earthing of the whole system, and the use of a fault

current protector (differential switch) in the circuit that's powering

this processor! Your life can well depend on it. I'm not the kind of guy

who warns everyone about all the stupid things they can do to kill themselves,

but in this case the warning is in order, because this project is specially

treacherous if incorrectly executed. Properly done, there is no risk. Last

time I checked, I still was alive!

How good are the results, you may ask? Well, the photos on this page were

scanned from slides developed in this machine, right after taking them. The

scans may look less than perfect, as the scanner is a pretty aged low-end

device, but I give you my word that the slides are excellent, with deep clean

blacks, the start of the film is completely transparent, the gradation

is rich, the colors are saturated and neutral, the grain is fine, there is

no dust (this was a real problem with several of the "professional" labs!),

and consistency over each film, and from one film to the next, or from one

session to the next, is impeccable. I'm really happy with home processing,

and with Tetenal chemistry!

And the cost? Chemistry, water and energy cost about 70% of having the film

developed by a lab. If I add the time (1 hour for 2 films), it ends up more

expensive, but hey, it's my leisure time, and that's free! And mounting the

slides at home costs 1/4 as much as having them mounted by a lab, and the

work is more carefully done, I assure you...

Back to the Homo ludens photographicus.

Before deciding on building such a machine, I looked at what's available

commercially. There are many options, most of them made by Jobo, but a machine

with reasonable features is depressingly expensive! A simple processor which

is nothing more than a plastic tank, heater, thermostat, circulation pump,

and rotation device for the tank, costs 5 times as much as a fully featured

computer-controlled automatic laundry machine that has all these things and

several more, and is several times larger and more powerful! The prices seems

rudely out of proportion!

Before deciding on building such a machine, I looked at what's available

commercially. There are many options, most of them made by Jobo, but a machine

with reasonable features is depressingly expensive! A simple processor which

is nothing more than a plastic tank, heater, thermostat, circulation pump,

and rotation device for the tank, costs 5 times as much as a fully featured

computer-controlled automatic laundry machine that has all these things and

several more, and is several times larger and more powerful! The prices seems

rudely out of proportion! Most commercial processors lack the capability for providing tempered rinse

water. But all color processes require rinses with tempered water! So, the

poor guys who buy a 1000 dollar machine need to spend additional money for

their controlled warm water supply! To get rid of such a problem, I used

a 30 liter bathtub as a container, and simply take water from it for the

rinsing. To compensate for the falling water level as the processing takes

its way, the rotation device is mounted on styrofoam floats, cut from the

packaging of my latest computer, thus holding the tank always at the same

level of immersion.

Most commercial processors lack the capability for providing tempered rinse

water. But all color processes require rinses with tempered water! So, the

poor guys who buy a 1000 dollar machine need to spend additional money for

their controlled warm water supply! To get rid of such a problem, I used

a 30 liter bathtub as a container, and simply take water from it for the

rinsing. To compensate for the falling water level as the processing takes

its way, the rotation device is mounted on styrofoam floats, cut from the

packaging of my latest computer, thus holding the tank always at the same

level of immersion. The stainless steel tank has no sealing, just metal-to-metal contact. So,

it leaks. And that's not nice. For that reason, I wrap the main joint in

electrical insulating tape. I use Scotch 33+, which is the best I have found,

and not only for this purpose. Highly recommended! It can be re-used many

times in this application. The tape not only seals the joint, but also eliminates

the risk of the tank opening due to a handling accident, and thus ruining

the films inside.

The stainless steel tank has no sealing, just metal-to-metal contact. So,

it leaks. And that's not nice. For that reason, I wrap the main joint in

electrical insulating tape. I use Scotch 33+, which is the best I have found,

and not only for this purpose. Highly recommended! It can be re-used many

times in this application. The tape not only seals the joint, but also eliminates

the risk of the tank opening due to a handling accident, and thus ruining

the films inside. The black box with the label is the circulation pump. It's intended for indoor

fountains, and I bought it for around 15 dollars at a Home Center. It is

fully submergible and runs directly off line voltage - a reason to be very

careful not to damage its cord! This pump maintains a vigorous agitation

of the water bath, resulting in very homogeneous temperature.

The black box with the label is the circulation pump. It's intended for indoor

fountains, and I bought it for around 15 dollars at a Home Center. It is

fully submergible and runs directly off line voltage - a reason to be very

careful not to damage its cord! This pump maintains a vigorous agitation

of the water bath, resulting in very homogeneous temperature. The controller is based on a Basic Stamp microcontroller. It contains several

film processing algorithms in memory, which can be selected from a menu.

The controller performs temperature control using a proportional-integral

characteristic and full phase control of the heater, resulting in fast warmup

time with minimal overshoot, and stable processing temperature. The temperatures

do not need to be set by hand, but rather they are included in the program

for each process.

The controller is based on a Basic Stamp microcontroller. It contains several

film processing algorithms in memory, which can be selected from a menu.

The controller performs temperature control using a proportional-integral

characteristic and full phase control of the heater, resulting in fast warmup

time with minimal overshoot, and stable processing temperature. The temperatures

do not need to be set by hand, but rather they are included in the program

for each process.